EALY MAYS RETROSPECTIVE

PRESS RELEASE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

ABXY presents: EALY MAYS | Retrospective Exhibition

OPENING COCKTAIL: THURSDAY NOVEMBER 16, 2017 | 6PM-9PM

EXHIBITION OPEN TO PUBLIC: FRIDAY NOVEMBER 17 – WEDNESDAY DECEMBER 22, 2017

Location: ABXY LES | 9 Clinton Street | New York, NY 10002

(NEW YORK, NY) On November 16th, 2017 ABXY will present a collection of paintings by the Paris-based, world- renowned artist: EALY MAYS. Mays is a painter’s painter for whom art is to be accessible to all. His work has been exhibited in such prestigious institutions as The Guggenheim Museum, (New York), the Louvre (Paris), Hammonds House (Atlanta), Galeria Clava (Mexico), and many more. ABXY is honored for the opportunity to exhibit a collection from this legendary outsider artist in New York for the first time in nearly a decade.

EALY MAYS is hailed as one of the most outstanding African-American artists of his generation. Born in 1959 in Wichita Falls, Texas, USA he was raised in Dayton, Ohio where he attended Fairview High School then returned to Marshall, Texas, where he earned a BSc. in Chemistry and Biology at Willey College. Mays never stopped painting and in the early 1980s he took a trip to the Caribbean Islands, which made a great impact on his later work.

At the age of 27 he was accepted to Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara School of Medicine in Mexico. He chose Mexico because he felt it provided the freedom to indulge his passion for art while in Medical School. It didn’t take him long to discover the local art scene where he met several celebrated artists such as RUFINO TAMAYO who would later become a mentor.

On his return to the United States, Mays was accepted for a residency at the prestigious SKOWHEGAN SCHOOL of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. Colleagues in residence included fellow artist ANISH KAPOOR, video artist GARY HILL, photo-artist NAN GOLDIN, and JACOB LAWRENCE, the most widely acclaimed African-American artist of the twentieth century. LAWRENCE became both friend and mentor, describing MAYS in a letter of reference to the Studio Museum in Harlem, as a ‘pure painter’, emphasizing his natural talent and his audacity in never following the crowd.

In search of “an intellectual environment to think, to breathe, and to paint,” in the late 1990s, Mays moved to Paris, where he was quickly invited as a permanent recurring resident at Cité Internationale des Arts.

As continued exhibiting in the USA and in Europe, international recognition of Mays’s work reached new heights. In both 2005 and in 2007, the artist’s series The Migration of the Superheroes was showcased at the Carrousel du Louvre, making Mays the second African-American artist (their first was Henry Ossawa Tanner in 1897) to have an exhibit in the modern gallery of the great museum.

Mays counts Jacob Lawrence, Jackson Pollock, Maxfield Parrish, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Rufino Tamayo, Herbert Gentry, Edward Clark (artist), and Franz Kline, as mentors.

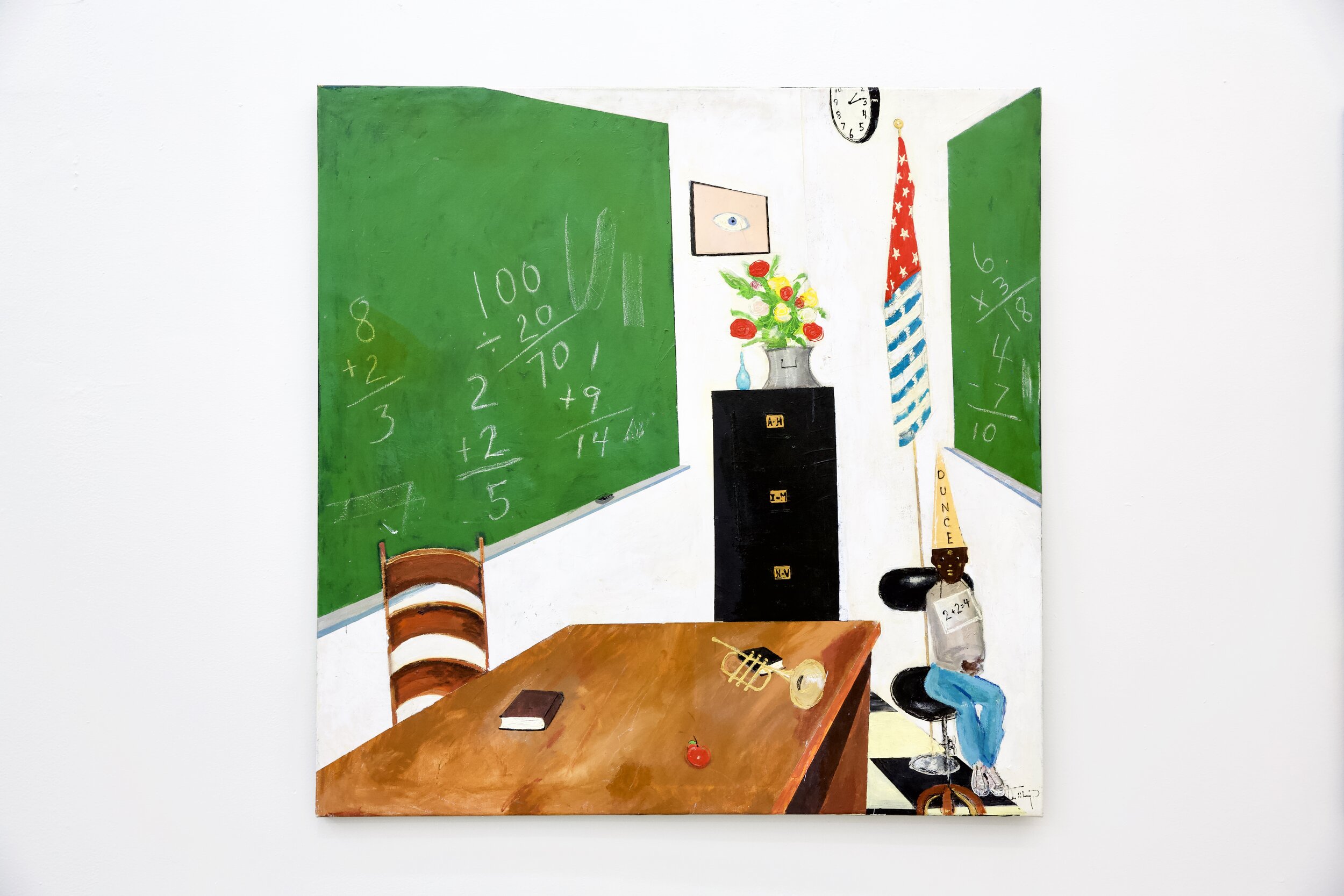

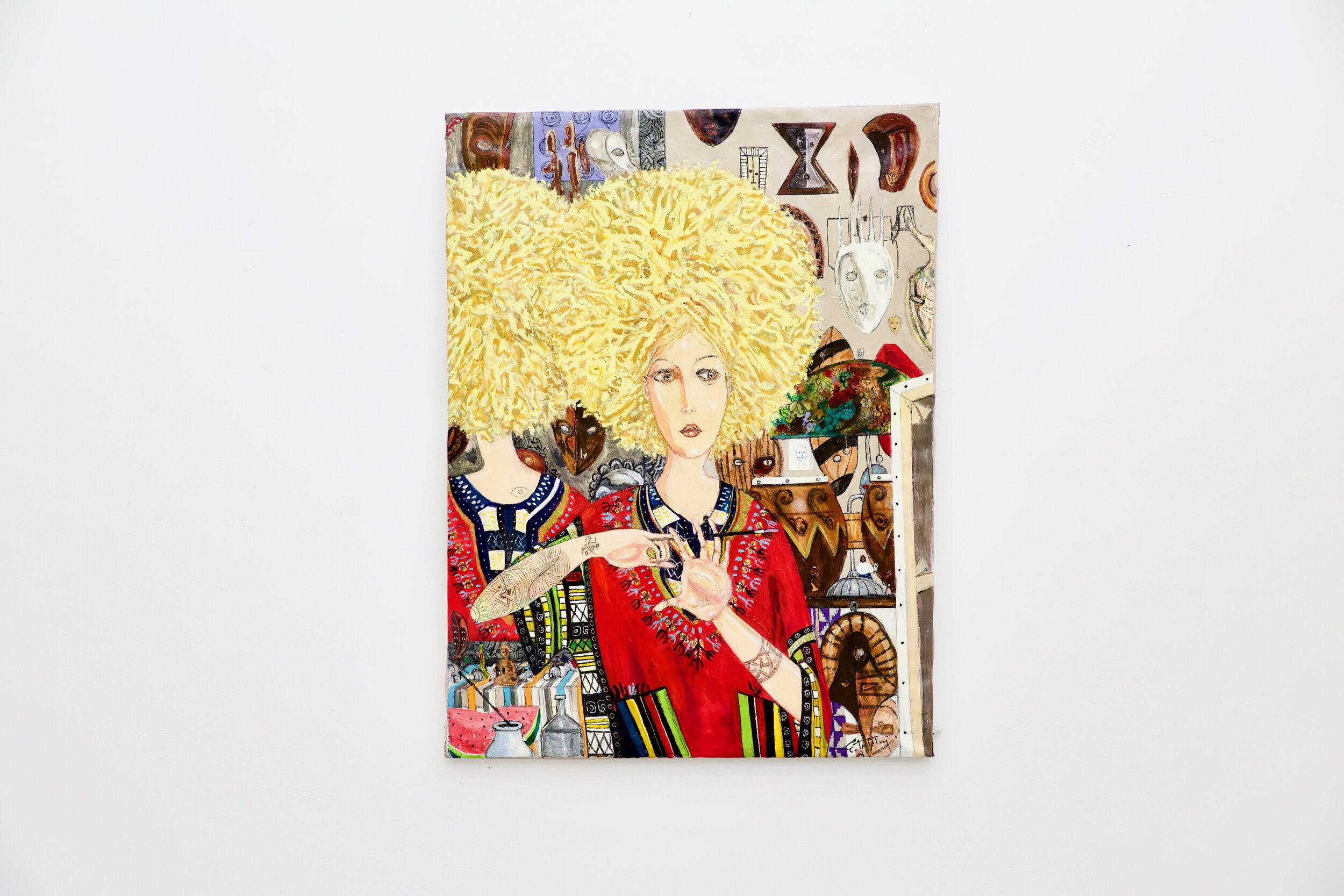

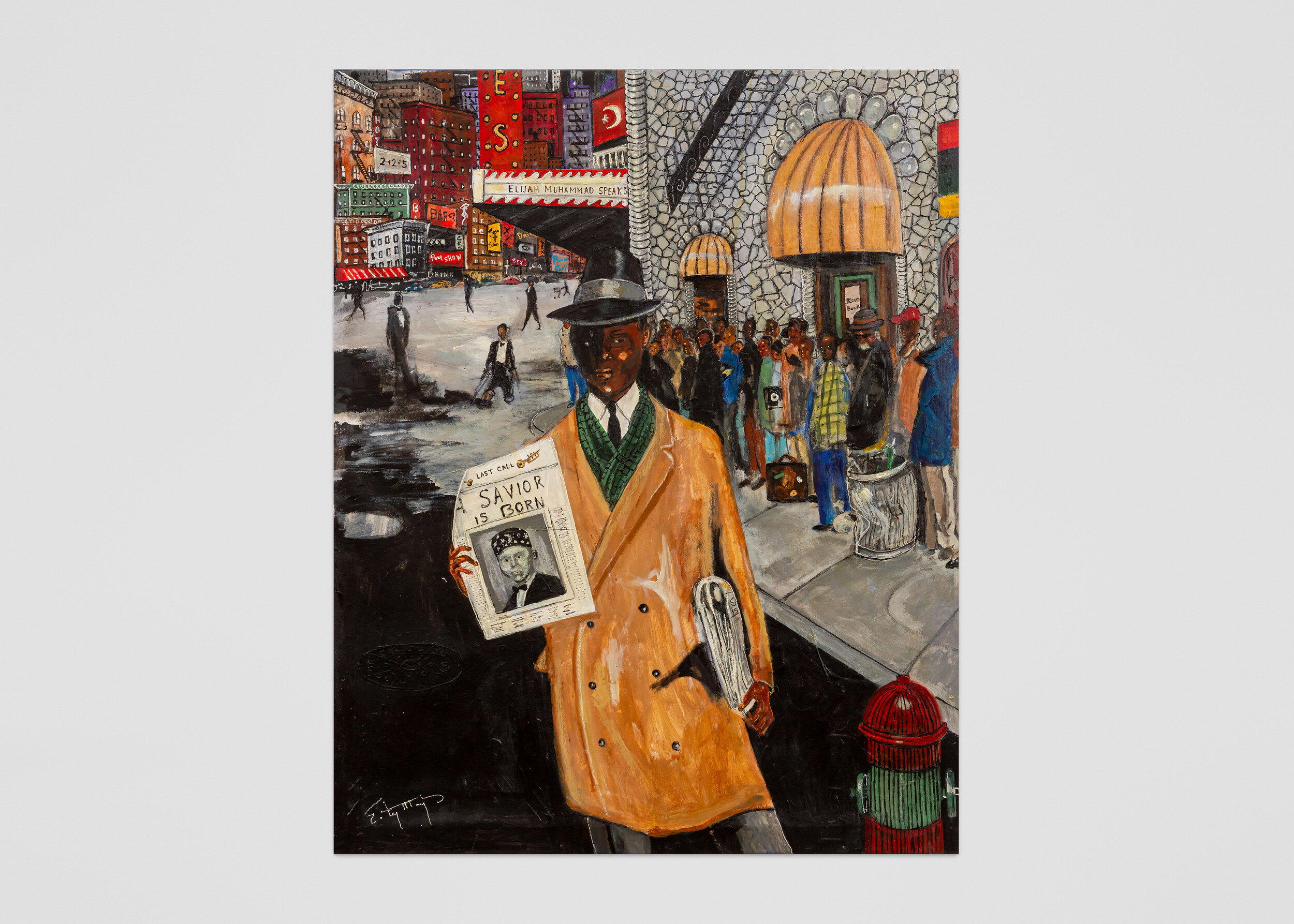

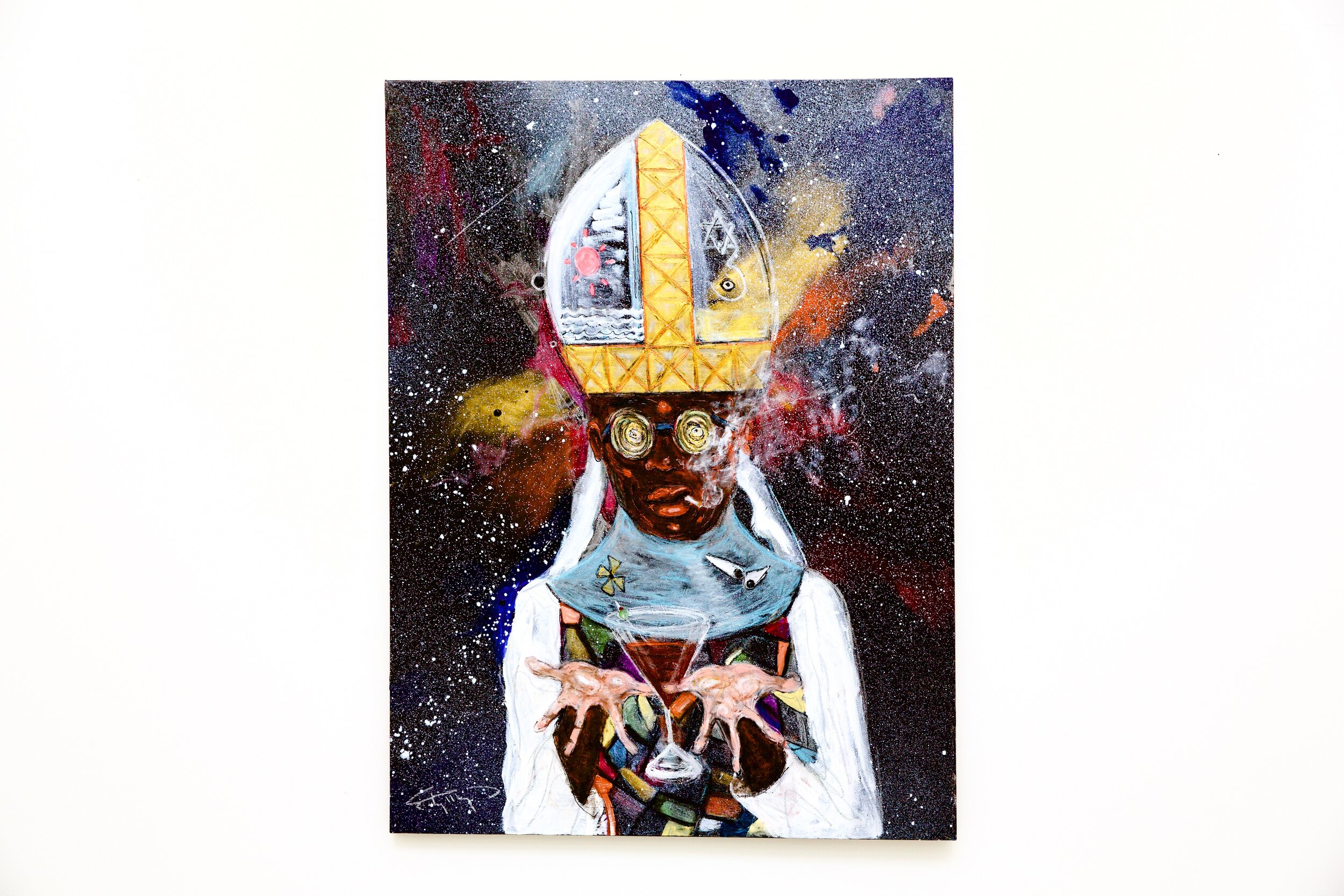

Ealy Mays sees himself as a social critic. His work embodies ethnicity, politics, history, religion, and satire. Mays’s social commentary and observations, take the viewer on an adventure around the world.

Although the creator of thousands of paintings, Mays is most proud of his single, best creation: his daughter.

Below please find an extended interview with Ealy Mays, first published in Whitewall Magazine, 2017

Coined a “narrative painter” by Jacob Lawrence at the prestigious Skowhegan Artist Residency, Ealy Mays creates meticulously detailed paintings, which animate history in a visual language all his own. His action packed canvasses brim with characters, movement, and symbolism. In Mays’ work, individual images tell the story of the various political events, technological developments, and cultural attitudes which result in the scene depicted. WW joined the artist to discuss his first solo show in New York and his upcoming retrospective at ABXY Gallery on the Lower East Side.

WW: When was your first solo show in New York?

EM: That was in 2009 at Fortissimo Gallery.

WW: What work did you show?

EM: I showed a lot of stuff. I like to show paintings from my different series together. They’re all connected in some way. I remember I showed, “If Everybody Thought the Same Nobody Would Think” and a prototype of “Migration of the Super Heroes,” (you have the real one in your show now), “Cajun Mama Queen,” A lot of Pokadotta Paintings. A lot of Mammy…

WW: What stands out to you about that show?

EM: About that show? Well, in fact most of the pieces I brought to New York for that show were stolen. 37 pieces.

I knew this guy from Paris who was supposed to pick up the pictures in New York. He picked them up and disappeared with them. Paul Sinclair was the name he used. I met him in Paris at a soiree. He lives here. In Columbus Circle. He even had the nerve – he’s got his address on the Internet, he claims to represent me. I thought he was one of my good friends. He claimed to be a financial investor. FBI and Interpol have the case now. It’s still going on.

WW: That’s terrible! Before they got stolen, what was the reception like?

It was great. I had a lot of heavy hitters there, big collectors of African American art. For example, Reggie van Lee, George N'Namdi, Brenda and Larry Thompson. Larry wanted a piece. He was the federal prosecutor under Reagan and the CEO of Pepsi Cola. They [later] underwrote my 2016 retrospective at the Hammonds House. When I saw him at the Hammonds House opening, he asked me about the painting he wanted to buy all those years ago from the New York show. It was one Paul had stolen. I still don’t have it back.

WW: What do you like about showing work in New York?

EM: The New York scene is never going to go out of fashion. Nor Paris nor London. Because there’s always a steady flow of different kinds of people coming here. These big cities are recess pools.

WW: What made you want to do a show in New York now?

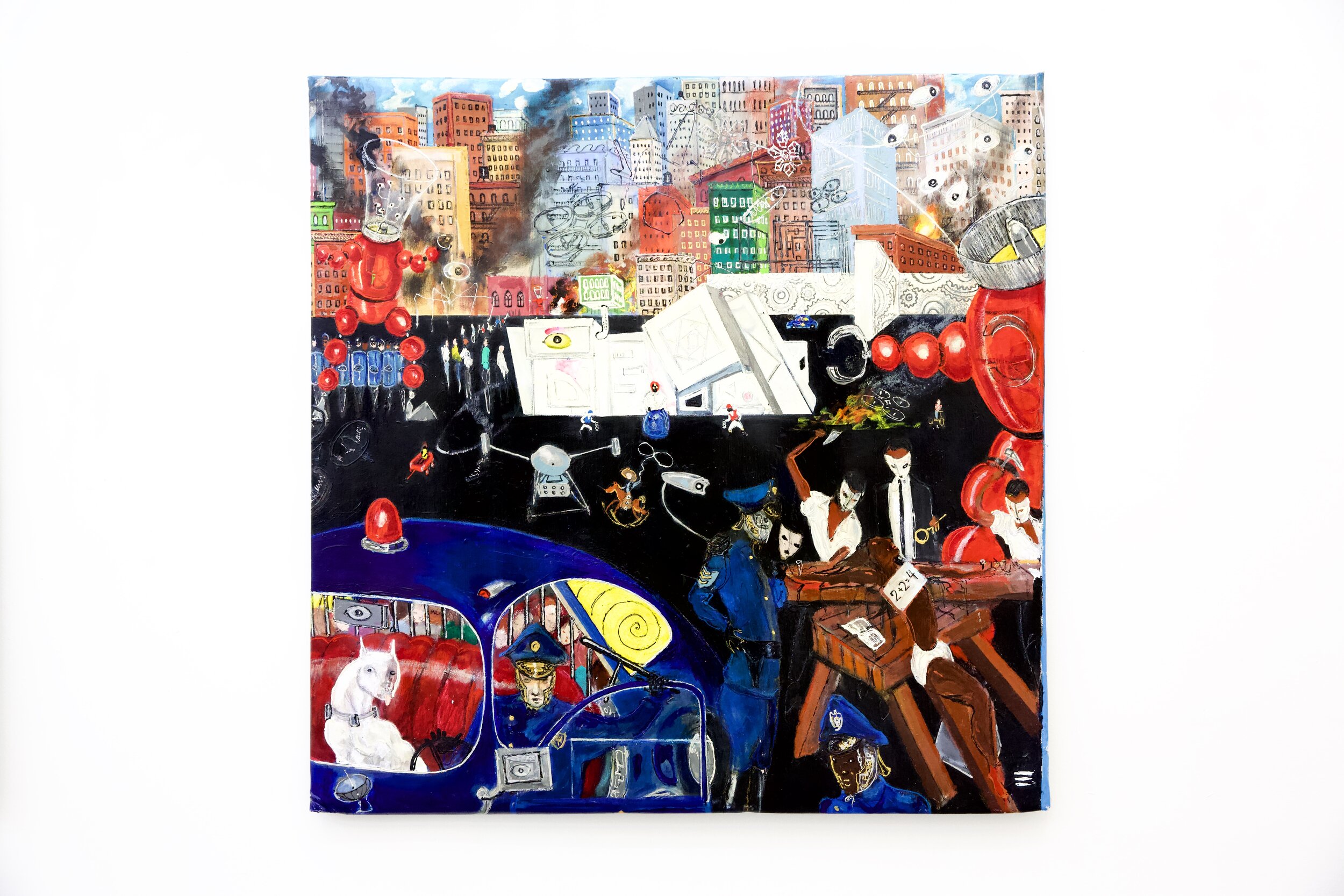

EM: I felt it was time for some new energy. Paris is not new energy. I’ve done a zillion shows in Paris. But cities that were destroyed like Moscow, or had bombs rained on them like London, it creates an energy that affects the art. Paris was never destroyed. Rome was never destroyed. 911 had a big impact on this city. That’s what Migration of the Super Heroes is about. (in current exhibition)

WW: What’s different about New York now versus New York in 2008? When you had your first solo show here?

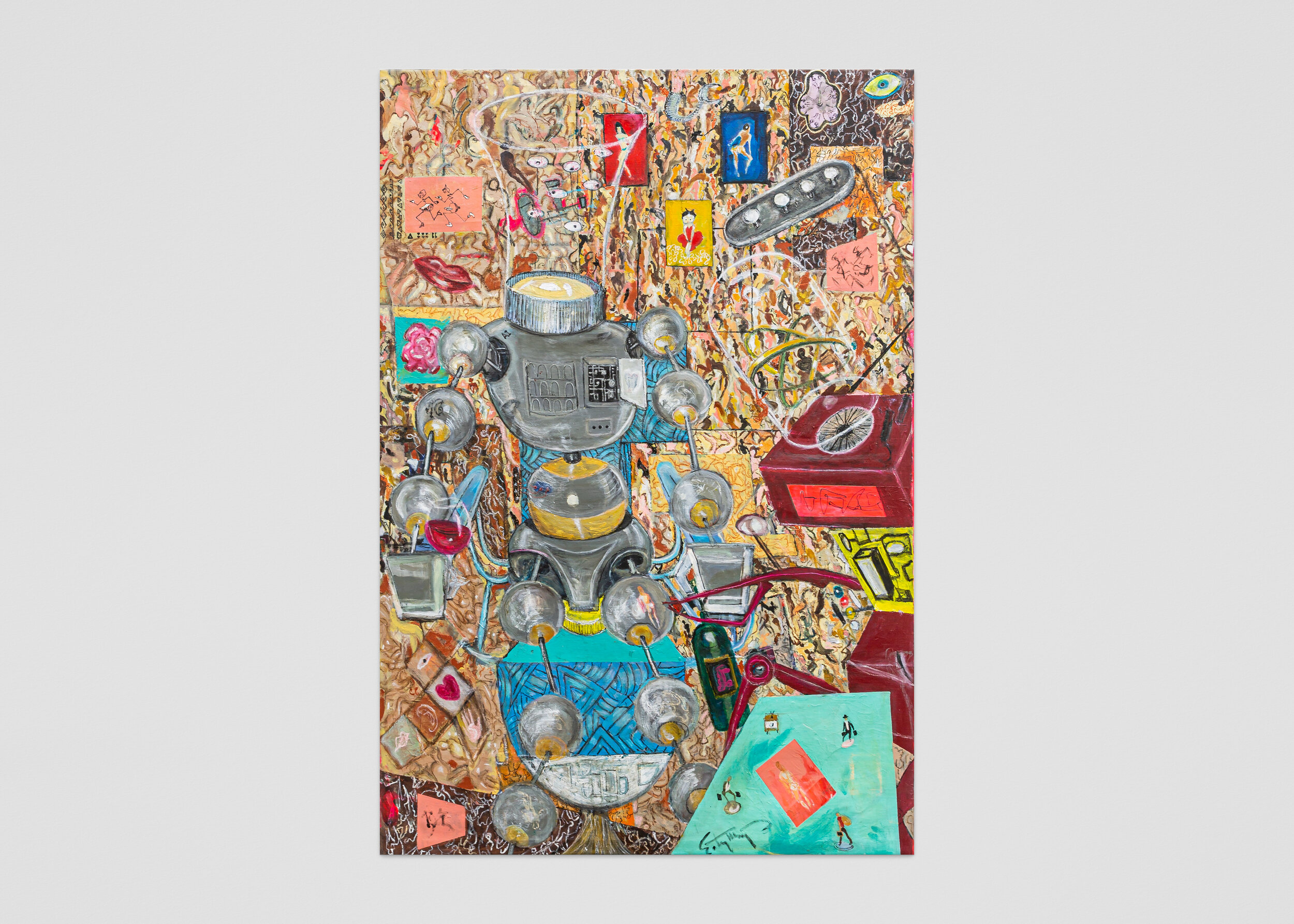

EM: Well a lot of the work in the show actually addresses this. A lot of it has to do with technology. It starts with “Migration of the Superheroes” which is about 911. It asks the question, where were our heroes that day? Because after 911, we experienced the rise of the police state and development of all these different policing technologies. That I deal with in “Live Like A Sheep Die like a Lamb,” it was inspired by an experience I had going through security in an airport in Houston…And then of course out of those policing technologies comes the development of artificial intelligence. That’s what “Robot with the Human Tattoo” is about. It’s a picture of a robot giving another robot a tattoo of a human figure. Because I’m interested in how artificial intelligence effects the human condition… I think the human condition is coming back in a big way.

WW: What other work will you be showing at ABXY?

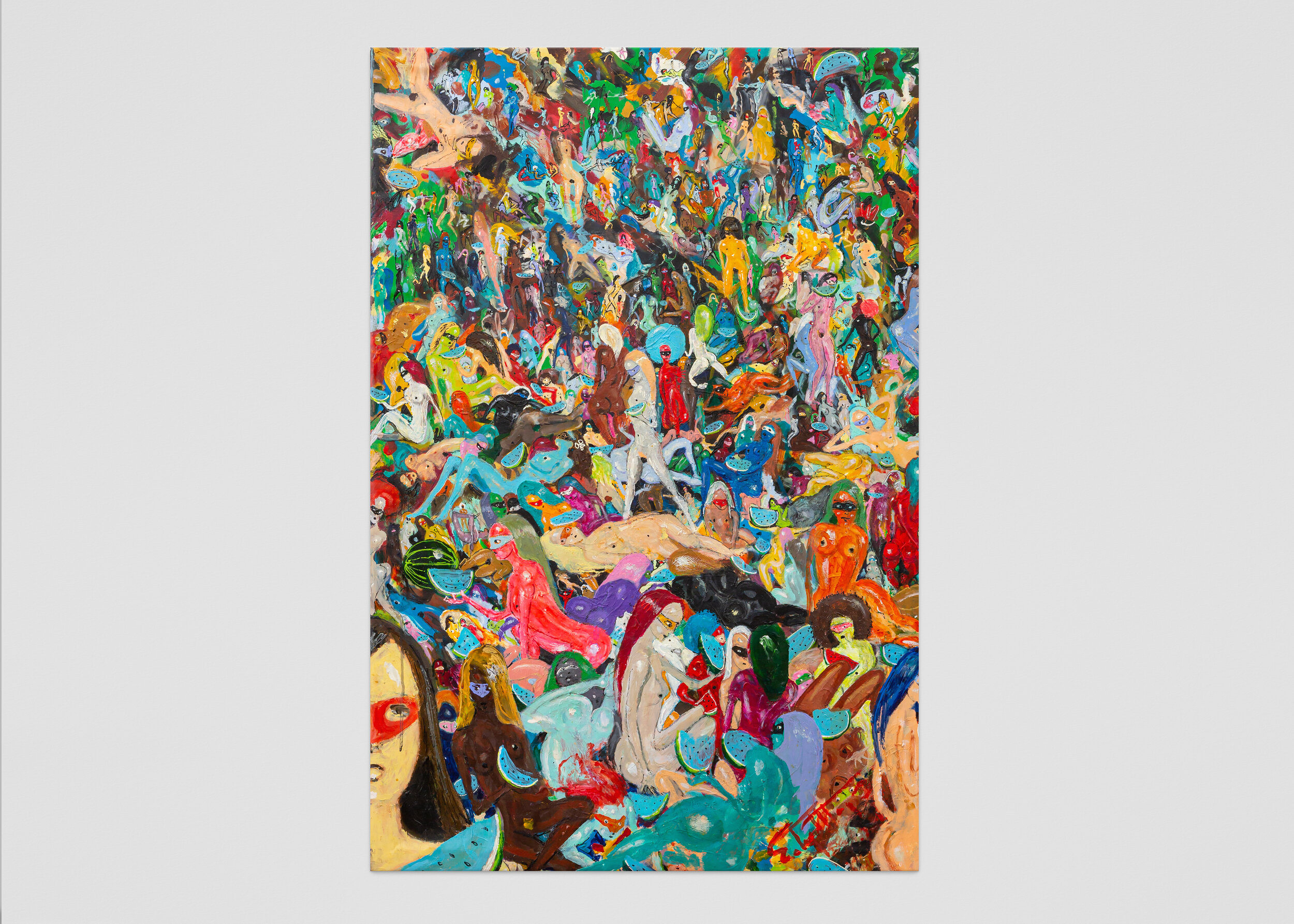

I keep going back to my recurring themes. For example, my Mammy series but I’m kind of fading away from Mammy, or my Blue Watermelon Series, but I’m kind of fading away from that too. I’m really focusing on my Cosmic series and my Polkadotta series.

WW: Why these series in particular?

EM: Because I’m in a reflective place. I want to make pictures about what’s going on today and I think the ideas behind those series apply to today. But I’m also at a point in my life and career where I’m looking back on my experience.

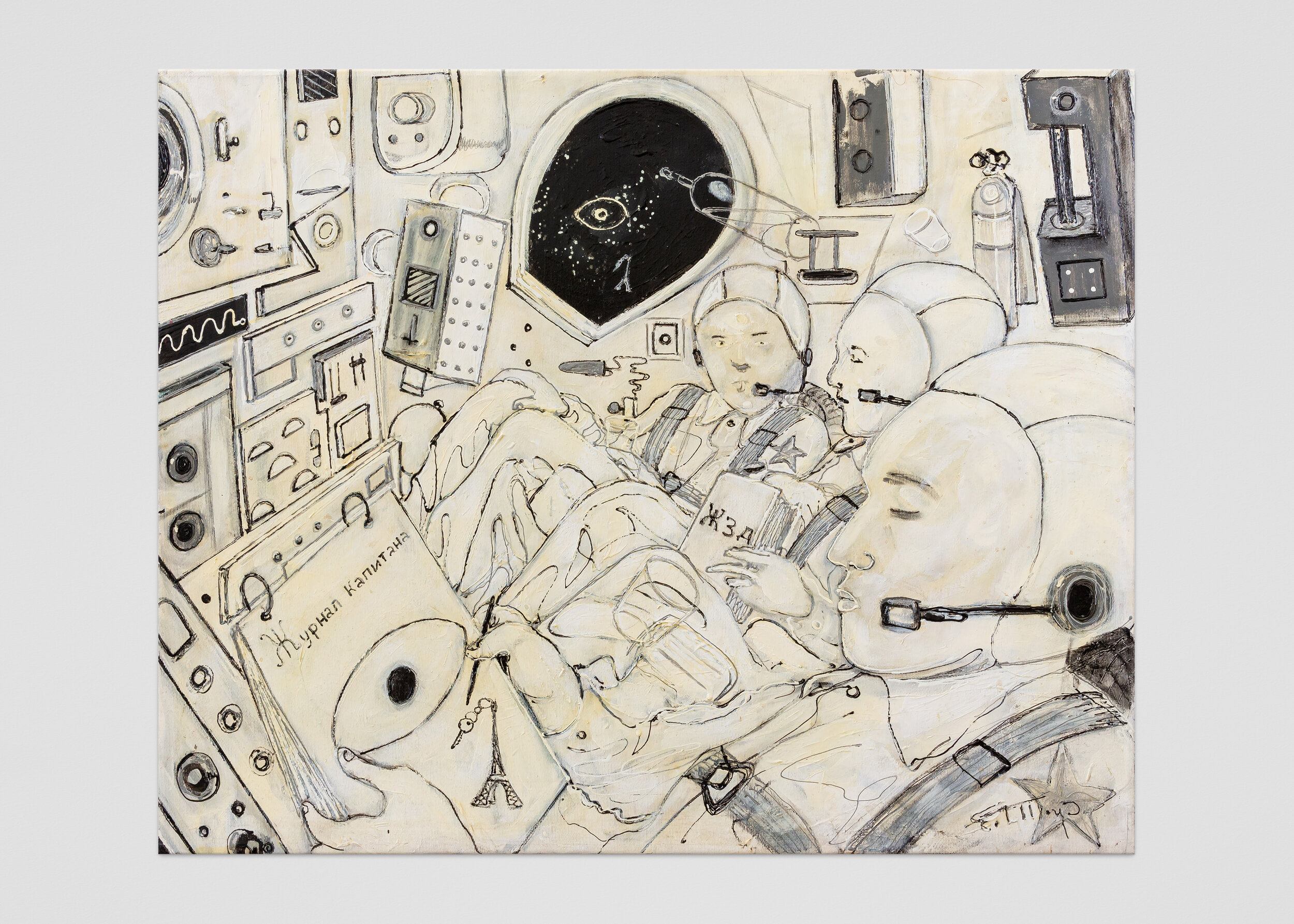

WW: Tell me more about the cosmic series.

EM: My cosmic series focusses on space and time and infinity. I was a product of the Cold War. I grew up with Nasa’s quest to the moon. And every Saturday morning we used to always watch the launches on television. When I was a kid we could only watch television for two hours a week. I remember some of the earliest programs we watched were The Outer Limits, The Twilight Zone and Star Trek. We all had telescopes. It was a time of fascination with the great frontier of outer space.

WW: Why come back to it today?

Well It’s something I can always expand upon but you know how they say ‘once a man twice a child?’ As a kid I used to draw spaceships and things of that nature. Now, having travelled around the world, I know, on a dark night anywhere on earth (that’s not a major metropolitan area), you can see thousands of stars. Looking at the stars always puts the petty things we fight about into perspective. There are infinite ways we are different but when we look at the stars we all always ask ourselves ‘what’s up there? That questioning is part of what makes us human. That’s something we should all think about today.

WW: You explore concepts of infinity in your Polkadotta series as well. Can you tell us a little more about that?

EM: The Polkadotta series was really developed out of my conflict with the figurative.

WW: What’s the conflict?

EM: Well there was none, until I went to Skowhegan. At Skowhegan, I was in conversation with all these very serious abstract artists like Anish Kapoor, Gary Hill, and Nan Goldin.

WW: What were you making at Skowhegan?

EM: I remember I made some big paintings. One of the Battle of Isandlwana – that’s when the Zulus were fighting the British Empire in South Africa. It was figurative work, in my style, images packed with symbols and references to history and the different histories that led the people depicted in the scene to the place they’re at in the image.

WW: What was the reaction?

EM: They did critiques in this building called The Little Red Barn. They ROASTED me in the first critique! But I didn’t give a damn. I was sticking with figurative. And Jacob Lawrence gave me a great critique – he called me a narrative painter – I was puzzled – I said what’s a narrative painter? But he meant that my paintings tell stories.

WW: How did these experiences lead to Polkadotta?

EM: Well, even though I didn’t change my style, my experiences with these abstract artists stuck with me. I remember Anish Kapoor showing us these rocks he was making with holes all over them. And I asked him what it was about but I didn’t get a definitive answer until he came to my studio. He was talking about black holes, infinity, and all that.

Then in 2008, I came across this sketch I had made in 1975, when I was in high school in Dayton, Ohio. There was a girl that I liked who was a modern dancer. I used to go watch her dance and I would sketch her in all these different positions. It was like ‘How many ways can you bake a chicken?’ ‘How many ways can a human body move?’ I always wanted to revisit the idea. I had since been inspired by the movements of Martha Graham and Alvin Ailey. And I found myself circling back to the idea of infinity.

So, reflecting on the conversations I had had with all of those abstract artists at Skowhegan, I started working out the mechanics – how I could make something look figurative and abstract at the same time – I wanted to paint the place where figurative and abstract meet and that’s how I came up with the Pokadotta series.

WW: Why are you coming back to this particular series now? How do the concepts behind it relate to what’s going on today?

EM: Well, traveling you know, you go through the airport, everybody has a different face, and every face for the rest of human history will be different from every other face, and you think, our being is infinity, our thoughts are infinity, and I like I said, I think the human condition is coming back in a big way.

WW: Can you give me an example?

So that painting called Black Spartacus Sports Protest – it’s comparing the great slave revolution that occurred in 59 BC in Rome to what’s going on in the NFL today. In Rome, the gladiators were slaves, forced to fight to the death for sport. They had been trained by the Roman soldiers but they rose up and revolted against the Romans. And it all started with one gladiator named Spartacus. What you’re seeing with the NFL– it’s really a glimpse into antebellum slavery – the owners can say to the players – if you don’t do this I’m gonna trade you to …. And what happened – the young man that protested – they said ‘he’s just a little nobody’ but it spread like wildfire – when a movement is in motion it’s like a tsunami – you can’t stop it – no matter how much money you throw at it – because when people harness the infinite power of the human spirit, it’s contagious and self-affirming. It’s people power.

WW: Why did you want to show at ABXY?

EM: Well many people I knew in the New York art scene from before are no longer with us. Some I just don’t want to work with anymore. This show is a retrospective but it also represents a shift. Shedding off the old bullshit. Like I said, I wanted new energy. And I like the energy of ABXY, the energy of the people who connected us, and your energy. With a lot of gallerists there’s a disconnect. You’re very generous to your artists, giving them studio space. I love being in the studio at ABXY. It’s always nice that I’m still around. The young boys can still listen to me. But it’s your time to create thunder.

WW: Do you feel your work relates to the work of the ABXY artists?

EM: Of course. It’s ironic that the Malik Roberts show right now is called “Stolen.” Because he’s painting pictures about what’s been stolen from black culture. I’ve [just put up] a new website about this whole stolen art thing. You may not get the art back but you can write about it. It’s the same with my work, I may not be able to change the story, but I can paint about it. So we’re after the same idea… It’s poetic justice.