OFFAL

SOLO EXHIBITION BY ARDEN SURDAM

Installation View | Offal | Solo Exhibition by Arden Surdam | Image courtesy of Erik Bardin Photography

PRESS RELEASE

ABXY presents:

OFFAL | Solo Exhibition by ARDEN SURDAM

OPENING: THURSDAY, JUNE 27, 2019 | 7 – 9 PM

ON VIEW: THURSDAY, JUNE 27 –WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2019

LOCATION: ABXY LES | 9 Clinton Street | New York, NY 10002

ardensurdam.com | @abxyles | abxy.co | Artsy

FOR ALL PRESS INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT MELANIE KIMMELMAN

(New York, NY) ABXY is pleased to announce Offal a solo exhibition by Los Angeles-based artist, Arden Surdam. Running through September 16th, the works in Offal invite us to consider the gendered, classified, racially dissonant narratives responsible for our own postcolonial notions of “good” taste (both aesthetic and culinary).

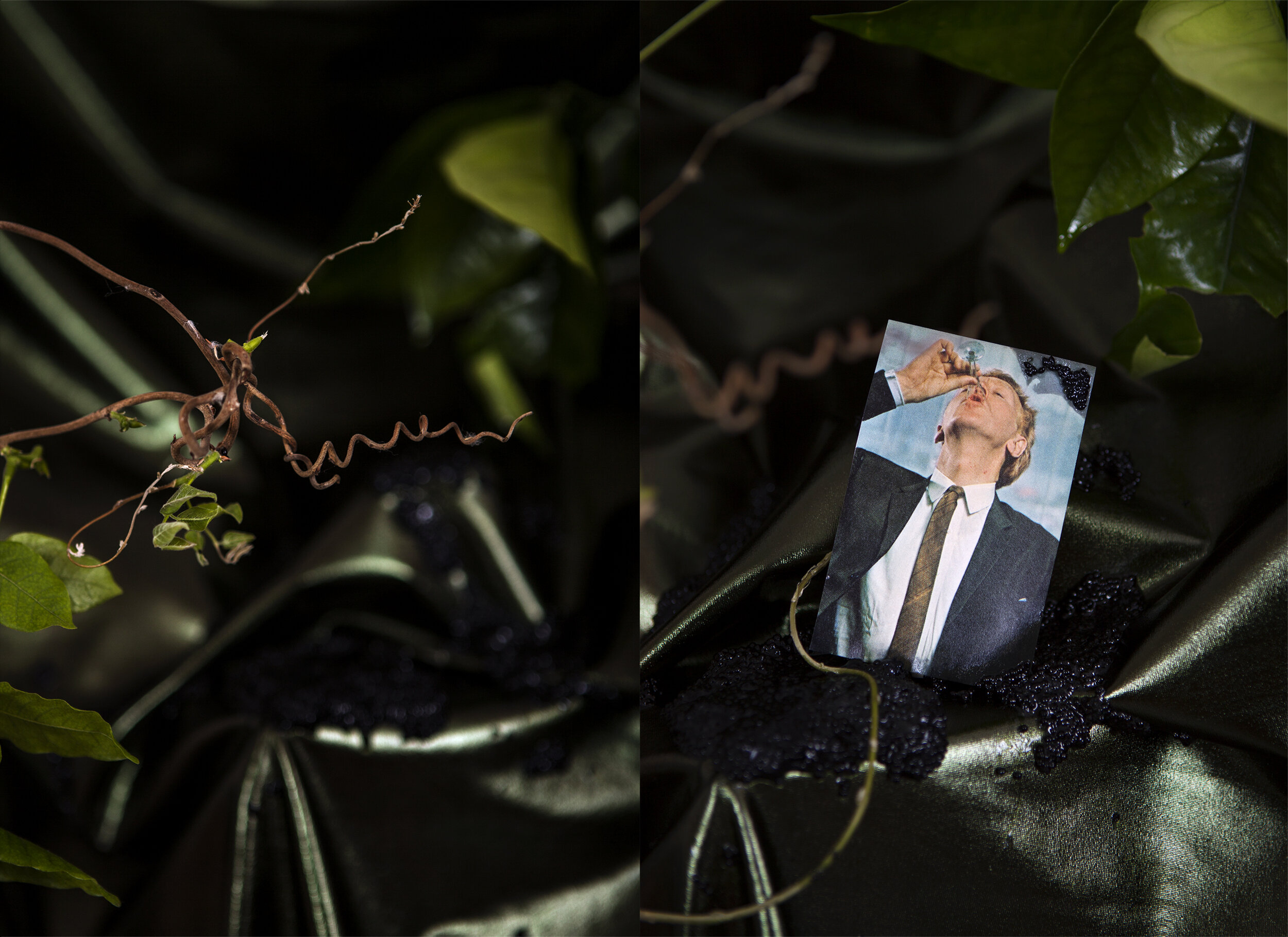

Offal denotes the entrails or internal organs of a recently slaughtered animal, intended for food. In her images, Surdam stages raw ingredients like liver, fish, and dead birds in scenes which recall the still life paintings of canonical masters like Chardin, Soutine, and Bacon. While set against elegant fabric backdrops within the glorified compositions of traditional genre paintings - here, food matter appears alongside burning etiquette books and sex-toys in disguise. By confounding our expectations of this historical art form, Surdam’s still lifes playfully tempt and offend our appetites, exposing tropes deeply embedded in our concepts of class and cuisine.

The artist frequently interjects pages torn from vintage American cookbooks into her gravity defying table-scapes, posing the active decay of organic matter in conversation with the saccharine vernacular of conventional gastro-pop-culture. By juxtaposing the grotesque realities of the kitchen with these tidy representations of meal prep, Surdam speaks to the ever growing physical and intellectual distance between earth and our dinner plates, farm and table, reality and illusion today.

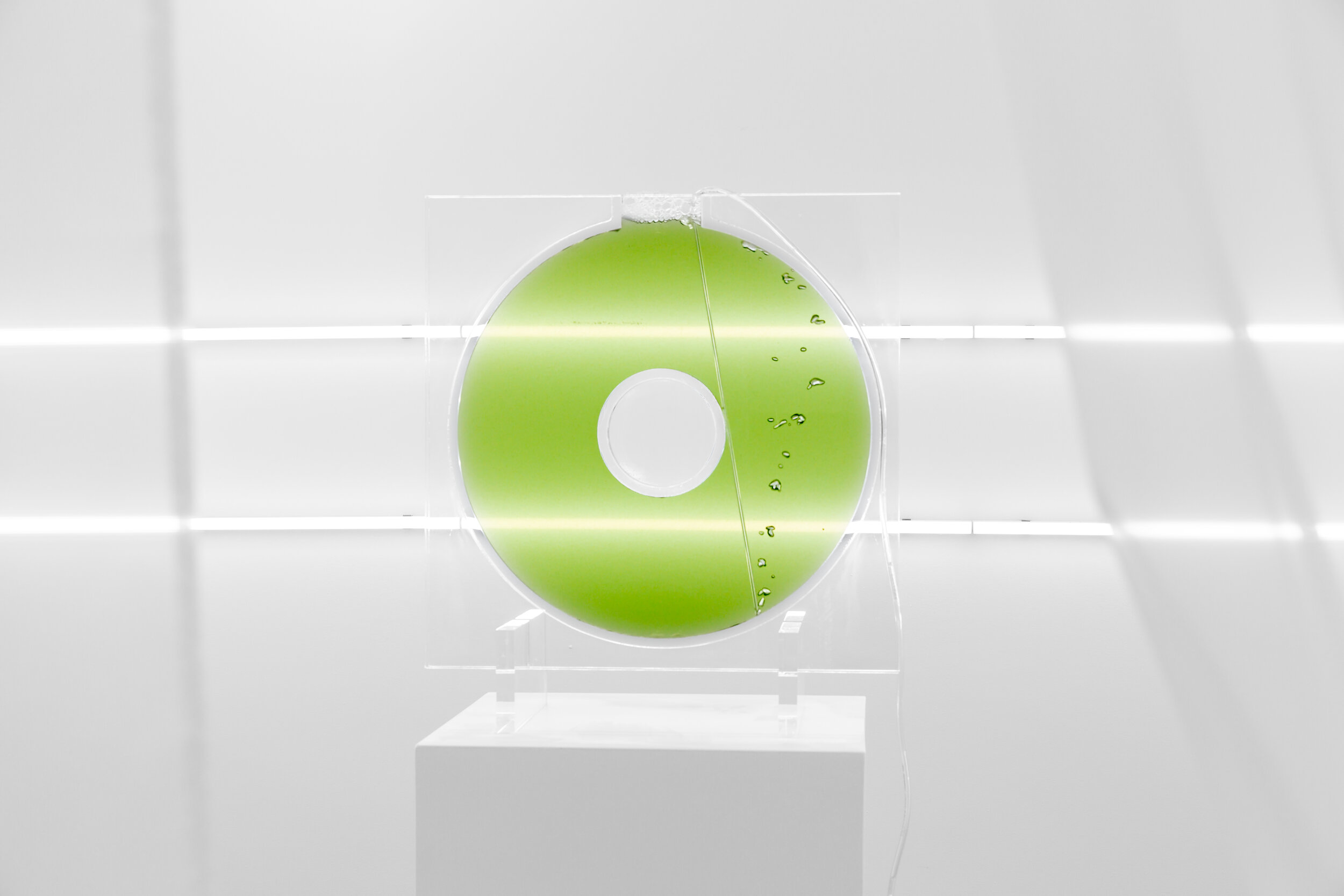

For Offal, the artist will also present a site-specific installation, which includes a donut shaped algae tank, filled with the trending cyanobacteria, spirulina. Today used as a dietary supplement for both humans and livestock, the growth will mutate continuously throughout the duration of the show, reflecting the volatility of our collective tastes.

Arden Surdam (b. 1988 New York, NY) received her MFA from the California Institute of the Arts in 2015 and her BFA from Oberlin College in 2010. Her work has appeared in GARAGE Magazine, CARLA, Tzvetnik, Singing Saw Press, Kubaparis, Paris Photo Parcours, TERREMOTO, and Photograph Magazine among other publications. Recent exhibitions include: NAUSEA, Galveston Artist Residency, Galveston, TX (2019); Hold Your Breath, SLOAN Projects, Los Angeles, CA (2017); Not All There, Human Resources, Los Angeles, CA (2018); A Curious Herbal, GARDEN, Los Angeles, CA (2017); Real Shadows for Mere Bodies, College of the Canyons with Stephanie Deumer, Santa Clarita, CA (2017); Exposed with Jo Ann Callisat the California Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA (2017); Paris Photo (2017), and Solid Liquid at The Situation Room, Los Angeles, CA (2016).

Exhibition Essay by Dr. Leonard Folgarait with words from W.M. Hunt & Efrem Zelony-Mindell

ARTIST STATEMENT

“My studio practice employs photographic methods to activate food matter. This occurs in multiple forms including social practice events, sculptural installations, and still life photography. My interest in food lies in its ability to be engaged as a social sculpture as well as a medium for sensory experiences. Moreover, I am fascinated by food's capacity to connote class, art history, and tradition. My most recent work for my 2019 exhibitions has been specifically focused on offal –the entrails or internal organs of newly slaughtered animals. I am interested in the historical use of these foods, most determinedly their cultural patterning and consumption by the lower class. The variable value of food by society, –an animal part considered precious in one century and collectively repugnant in another, is a fluctuating system of likes and dislikes that has become a focal point of my current practice.

In my latest works, I have inserted food matter like liver, ray fish, oysters, and pig intestines into traditional still lifes. This gesture, inspired by the canonical images of Soutine, Bacon, and Chardin, is intended to visually signify the tension between delectability and repulsion. In addition to food materials, the still lifes feature photographs taken from the pages of American 1970s international cuisine cookbooks, which present visual directions on how to cook “sophisticated” intercontinental meals. By re-photographing these images, my desire is to challenge the intentionality of ‘food worldliness’, questioning traditional notions of value through ideas of food loathing (elementary and archaic forms of abjection) and food worshipping.”

- Arden Surdam, 2019

Arden Surdam, ABXY Gallery, 2019 (Image courtesy Maverick Inman)

EXHIBITION ESSAY

Who, What, When, Where, How

by Dr. Leonard Folgarait

Distinguished Professor of History of Art

Vanderbilt University

ARDEN SURDAM, Context Collapse, 2019 INSTALLATION VIEW Courtesy of Erik Bardin

Something is burning that should never be burnt. Fine fabric, elegantly draped, the very sign of sophisticated privilege, should never start smoking. Something is terribly wrong here: we don’t want to see this but somehow feel forced to see what happens next. Will the fire brigade, agents of our institutionalized security, show up to put it all right again? An animal seems to be in a state of distress due to our interventions into its otherwise normal existence. Oh, that’s ok, as we have the right to torture, kill, cook and eat other animals. Instructional photographs torn from history’s innumerable manuals are proof that we have these rights and that we have all the tools that we need to do it right, to choose the right de-boning knife, to cook at the right temperatures and to conduct taste tests.

I’m sure that the artist, Arden Surdam, will take wicked delight in some gallery visitors walking away saying, “That was an offal show.” That phonetic slip sits so comfortably with the manner in which these images refuse(!) to assert the comfortable binaries of our visual and social existence, how they confound the hierarchies of systems of authority, and leave us floating in unresolved tensions, as all art that matters should do. And art that matters should conserve that list of inquiring words, which make up the title of this essay - as unanswered, and rather simply stated, concepts beyond both question and answer.

OFFAL | Opening Night, Image courtesy of Erik Bardin

These images invite us into a world that is not usually photographed and that does not satisfy the main tenet of the photographic image: that it must have existed in some form before the shutter, mechanical or electronic, clicked to capture some sense of that original condition. Photography lures us into that fictitious expectation that it somehow stands as a witness to and recorder of reality. Not so, not even from the earliest days of this medium, when busy city streets looked deserted as the long exposures blurred and erased thronging pedestrians. Consequently, early photographers favored already very still images, such as still life elements on table tops and dead bodies on US Civil War battlefields.

Surdam, while employing digital technology to capture her images, falls back on this realization, that photography is ultimately better suited to dead-still images. She pushes our visual sensibilities forward to new viewing experiences while pushing our historical sensibilities backward, leaving us hanging in this temporal tension, its irresolution forcing us to look even more closely and to dive into that phenomenological vacuum. So, what do we see?

First, we don’t see, but rather feel the image, more accurately, our spatial position in regard to the image, and even more precisely and suggestively, how the image positions us into a spatial limbo where up and down and left and right and other normally dependable coordinates of our body in space fall by the wayside. ‘Normal’ photography does just the opposite, placing us firmly on solid ground. These images are photographs but do not behave as photographs, and their content reminds us that we humans are not always humane.

They behave, rather, like still-life paintings by Paul Cézanne of the 1880s, when he presented multiple perspectives on a collection of fruit on a table top, the two leading corners on divergent axes, and a white tablecloth covering the front edge of the table, exactly, conveniently, where the break in the solid table purportedly happens. This reference to Cézanne contributes to undermining photography by reference to painting, and also seems to explain why Surdam depends so much on fabric, voluminous drapery, suspended or deposited in convoluted folds that defy gravity and release it and its companion objects from objective spatial positioning.

ARDEN SURDAM, Still Life With Ray, 2019

This is all a subversive, interventionist operation on the bourgeois-liberal ideology of realism and the perspectival logic that supports it. Single point perspective promises us access to a fictive world, one that we seem to occupy and control on the basis of its resemblance to our normal, real world. Starting with Edouard Manet and Cézanne, through Malevich, Kandinsky, Rothko, Goncharova, Frankenthaler, and now Surdam, that umbilical cord to a false world is blown to smithereens, as is belief in that world itself.

This release can produce two results in the viewer, either; a state of panic and utter desperation at being cut off from all systems of ideological and psychic support, left unmoored to float in a directionless space; or one of existentialist freedom, a sudden discovery that we can, after all, let go of virtual shackles and ideological prisons and discover what our own reality is all about, what it has always been all about.

If we now have our own reality, so too does the artwork, as an objectively real, two-dimensional surface, declaring a philosophy of truth in counter to the lies told to us by ‘realism’ and its enforcer, perspectival space.

ARDEN SURDAM, The Buffet, 2018

This new-found freedom feels and looks different, as different as possible from the visible world while still clearly referring to it, yet illuminating that world with newfound realizations. Surdam’s achievement puts me in mind, of course, of the photographer Garry Winogrand’s quote, “I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed.” He means looking more truthfully, perhaps. To the novelist Joseph Conrad, art is “a form of imagined life greater than reality,” and its purpose is “to render the highest kind of justice to the visible universe.” Winogrand, Conrad, and Surdam achieve this very necessary goal, especially in our times of massive challenges to clarity of thinking, aesthetically and politically.

ARDEN SURDAM, Liver i, 2019

So, a lot of this has to do with consumption: of food both visually and digestively, of still-lives as food for the purpose of display, of the right to waste food by using it to stage one’s ‘taste,’ and of art in general as objects of desire / investment / bragging rights to have snared a hot new artist. What does it mean to look at food, to record it by photographic means, to not eat this imaged food? And then, of course, the challenge to eat organic matter in states of some violence, or simply as raw, disgusting, inedible; challenging our ideas of measuring the sophistication of society by what we eat and don’t eat. The slaughtered animal, while still alive, valued all of its own organs equally, but we, who have given ourselves the right to torture and to kill animals unnecessarily, have felt entitled to pick and choose what parts to eat and what parts to turn away from. Some segments of our populations do not, however, experience these entitlements and instead are forced by circumstance to mix these organs into stews and watered-down soups. These are the menu choices of stratified societies.

ARDEN SURDAM, Chicken Hanging Before Red Wall, 2019

“Chicken Hanging Before Red Wall” is so beautiful as an image, yet so blatant a challenge as to the job of the viewer. What are we to ‘do’ with this image: admire the obvious and delectable celebration of surfaces, brilliant light control, juxtaposition of textures; or be repulsed by some obligatory and unconscious recognition of the vulgarity and gag factor of it all, the red as blood, the chicken as perhaps still partly alive; or be so totally disoriented by the spatial insecurity of the image as to ignore all the above? In either and any case of all these options, Surdam forces us to ask these questions at such an intellectual and emotional depth that we feel to be drowning and in desperate need or air and resuscitation. This is so radically alien to any experience or memory that we might have that it needs to be considered on its own terms, but what are those? A violently treated animal, fine crystal, the odor of decay, fine drapery now despoiled, our eye hovering (above, in front of?), our hands partly covered with plucked feathers, perhaps holding a butcher knife, deciding what to do with the slimy internal organs (maybe stage them as a still-live photograph?!); the list becomes endless because of infinite possibilities and because the human mind, fighting its socialized tendencies, cannot control the chaos that ensues.